Stone Gardens : Old Settler governed the Nation during a critical phase of Choctaw resettlement from 1850-1852

- Dennis McCaslin

- 1 hour ago

- 4 min read

s you navigate the winding dirt roads of southeastern Oklahoma's LeFlore County, the landscape unfolds like a forgotten chapter from a history book. Towering pines and oaks cloak the rolling hills of the Ouachita Mountains, and the air carries the faint scent of earth and wildflowers.

This is ranch country now--vast, private spreads where cattle graze under endless skies. But tucked away on one such ranch, accessible only with permission and a sense of reverence, lies Wadesville Cemetery, a remote sanctuary of weathered stones and silent stories.

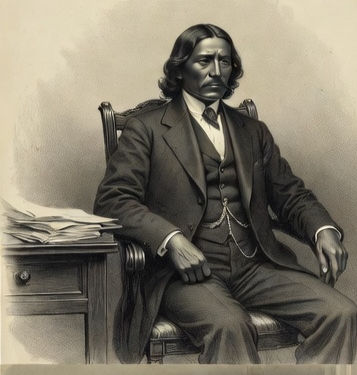

It's here, amid the overgrown plots and faded inscriptions, that we pause to reflect on the life of Chief Thomas Wade (1813–1893), a pivotal figure in Choctaw history whose grave marker stands as a quiet testament to resilience, leadership, and the enduring spirit of adaptation.

Imagine approaching the cemetery on a crisp autumn morning, the crunch of gravel underfoot giving way to soft grass. The site is modest, encompassing about 50 graves, many unmarked or eroded by time. Established in the mid-19th century, it's the final resting place for early Choctaw settlers who braved the Trail of Tears.

At its heart is Wade's headstone, a simple yet poignant slab etched with words that capture his extraordinary journey: "Thomas Wade, Ex. Governor of the Choctaw Nation. Who immigrated to this country, finding it a rude wilderness destitute of all that makes a true civilization. Deceased 1893."

Born in Mississippi around 1813 as a full-blood Choctaw, Wade's early life was rooted in the ancestral homelands of his people, a world of communal clans, matrilineal traditions, and deep connections to the land.

But the 1830s brought upheaval. Under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830), the Choctaw were among the first of the Five Civilized Tribes forced to relinquish their eastern territories for promises of autonomy in Indian Territor;

. Wade, then in his late teens or early twenties, joined the exodus, navigaing a harrowing migration marked by disease, starvation, and loss. Thousands perished along the way, but Wade survived, carrying with him the unyielding resolve that would define his legacy.

Settling in what became known as Wadesville (a short-lived Choctaw community in the Apukshunnubbee District, Wade transformed the "rude wilderness" into a thriving hub of adaptation. The area, near the modern town of Talihina, was raw and untamed, with dense forests and untapped resources.

Wade, drawing on Choctaw ingenuity, helped establish farms, trading posts, and social structures that blended traditional ways with the necessities of frontier life. By the 1840s, he had risen as a leader, advocating for his people's rights amid the chaos of relocation.

In 1850, at the age of about 37, Wade achieved a milestone: he was elected governor of the Choctaw Nation, serving a single term during a critical period of reorganization. The nation had recently adopted a new constitution in 1842, shifting from district-based chiefs to a more unified government with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. .

As governor, Wade navigated tensions between traditionalists and progressives, oversaw land allotments, and pushed for education and infrastructure—efforts that laid the groundwork for the Choctaw's survival as a sovereign entity. Though his term was brief, it coincided with the nation's push for stability post-removal, earning him the enduring title of "Ex. Governor" on his gravestone.

Wade's personal life mirrored the complexities of Choctaw society, where family ties and polygamous marriages were common, reflecting cultural norms that emphasized kinship and community support. He had multiple wives, each contributing to his household and legacy.

His first known wife was A-Ho-Yo-Te-Ma (meaning "to give forth" in Choctaw), a name that evokes generosity and nurturing, all qualities essential in the harsh post-removal era. Later, he married Nancy (1813–1860), who shared his journey until her death at age 47, possibly from the rigors of frontier life.

His third wife, listed simply as "Mrs. L. T. Wade" (1826–1876), joined him in building the family homestead. Wade also had a brother, Cornelius, whose presence in the records underscores the tight-knit bonds of Choctaw clans

. Children and extended kin, including possibly Alfred Wade (1811–1878), a relative buried nearby, formed the core of Wadesville's social fabric. The community even boasted a post office from 1877 to 1884, a nod to its brief vitality under Wade's influence. Family graves cluster around his, including Nancy's and L. T.'s, creating a poignant family plot that speaks to love, loss, and continuity

.Wade's legacy extends beyond his governorship, embodying the Choctaw ethos of perseverance. He helped foster early Choctaw adaptation, from establishing missions and schools to negotiating with U.S. agents during a time when federal policies threatened tribal sovereignty.

The naming of Wade County (one of the original Choctaw counties, later absorbed into LeFlore County) honors his contributions, as does Wadesville itself, a ghost town now, but a symbol of early resilience. In politics, he bridged the old district system (where chiefs like Thomas LeFlore held sway) and the emerging unified nation, influencing successors like Alfred Wade (governor 1857–1858) and Tandy Walker.

His work in governance helped preserve Choctaw identity amid encroaching American expansion, setting precedents for land rights and self-determination that echo in today's Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

.Yet, it's Wade's death and burial that bring us full circle in this cemetery walk. He passed in 1893 at age 80, likely from natural causes after a life of service and hardship. The year was tumultuous for Native Americans—the Dawes Act (1887) had begun dismantling communal lands, leading to allotment and statehood pressures that culminated in Oklahoma's formation in 1907. Wade's death marked the end of an era, but his interment in Wadesville Cemetery ensured his story endured.

The site, now on private land, requires respectful coordination to visit, adding to its elusive allure. Standing before his stone, one can't help but reflect on the irony: a man who tamed a wilderness now rests in seclusion, his grave a whisper amid the pines.

As the sun filters through the branches, casting long shadows over the plots, Wade's epitaph reminds us of the human cost of progress and the quiet dignity of those who forged nations from the wild.

Chief Thomas Wade's grave isn't just a marker; it's a portal to the Choctaw past, urging us to honor the leaders who walked the trails of tears and triumph. If you venture here, tread lightly--the wilderness, though civilized, still holds its secrets.