True Crime Chronicles: A train heist in Mulberry that led to a death and the hanging of four outlaws in Clarksville

- Dennis McCaslin

- Oct 25

- 3 min read

In the quiet hills of western Arkansas, where the railroad cut through the coal country of Crawford County, a small town called Mulberry became the scene of a deadly crime in 1883. On March 7, four men tried to rob a train on the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, hoping to steal a rumored $10,000 payroll.

Their plan went wrong, leaving a train conductor dead and leading to their own execution.

The leader was Gove Jackson, a 36-year-old farmer from Johnson County. Born in Kentucky, he’d fought for the Union in the Civil War and carried a grudge against railroads, blaming them for hard times after the war. He heard about a southbound train carrying cash and convinced three others to join him: his 19-year-old cousin James Johnson, a young farmhand; James Herndon, 28, a local worker; and Monroe McDonald, 33, another farmer.

They were poor, tempted by the promise of quick money, but Herndon and McDonald later said they were scared of Gove and felt forced to go along.

That evening, the four boarded the train in Mulberry, carrying pistols and shotguns. Their plan was simple: stop the train in a lonely stretch, scare the passengers, and rob the express car’s safe. But things fell apart fast. When they approached conductor William Cross, a 40-year-old from Fort Smith, he refused to stop the train. Cross pulled his gun, and in the chaos, Gove shot him in the chest with a shotgun.

Cross died on the spot, collapsing between the cars as passengers screamed. The robbers searched the express car but found only about $300, far less than they’d hoped.

With gunfire alerting nearby farmers, they ran off into the woods, leaving the train stalled.

News of the murder spread quickly, and people were furious. The Arkansas Gazette called it a terrible crime, demanding the culprits be caught. Within days, posses from Fort Smith, Clarksville, and Little Rock, along with Pinkerton detectives hired by the railroad, tracked the men down.

Gove and James were caught hiding in a barn on March 10. Herndon and McDonald turned themselves in soon after, saying Gove made them do it. The railroad and the state offered $2,000 in rewards, which helped speed up their capture.

The trial took place in Clarksville in April 1883. Passengers and the train’s engineer testified about the robbery and Cross’s death. Herndon and McDonald admitted they helped but blamed Gove for the shooting.

The jury didn’t care about their excuses and all four were found guilty of murder on May 15.

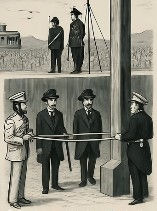

Judge Jacob Walker sentenced them to hang on June 22. The governor refused to pardon them, as the public wanted justice for Cross.On June 21, the men were brought by train to Clarksville, where a huge crowd of about 5,000 people gathered to watch.

The hanging was set up outside the Johnson County jail, with bleachers for spectators and vendors selling snacks. On June 22, at noon, the four men walked to the scaffold, guarded by soldiers.

They wore black suits and listened to a preacher’s prayers.

Gove said he didn’t shoot Cross and blamed the railroads. James asked Cross’s widow for forgiveness. Herndon and McDonald said they regretted following Gove.

At 1:15 p.m., the trapdoors opened, and they were hanged.

They were dead in minutes, and their bodies were buried in unmarked graves by their families.

The Mulberry Train Robbery was one of Arkansas’s last big train heists. It led to tougher laws against robbing mail trains and more guards on railroads.

A marker near Mulberry remembers William Cross as a brave man

. The hanging of Gove Jackson, James Johnson, James Herndon, and Monroe McDonald on June 22, 1883, became a warning to others: crime in Arkansas’s rough frontier days came with a heavy price.