Stone Gardens: Soldier from the Sab Bois Mountains immortalized through Purple Heart and WWII comic strip

- Dennis McCaslin

- 9 hours ago

- 5 min read

In the muddy foxholes of World War II Italy, where the 45th Infantry Division's Thunderbirds clawed through the Apennine Mountains and faced the brutal grind of the Italian Campaign, one man's quiet resolve and wry wisdom left an indelible mark on history.

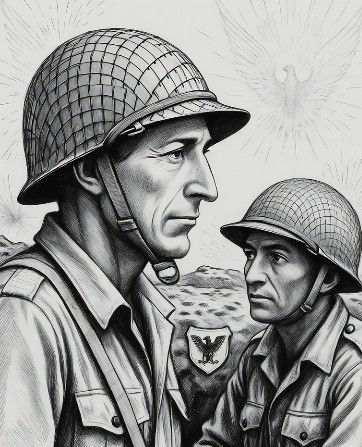

He wasn't a general barking orders from a command tent, nor a headline-grabbing hero storming beaches under fire. Rayson John Billey-- known to friends and comrades as "Billey" -- was a sergeant from the rolling hills of eastern Oklahoma, a Choctaw code talker whose intellect and grit inspired the iconic cartoon character "Willie," half of Bill Mauldin's beloved duo "Willie and Joe" cartoo strip.

These mud-caked GIs, with their stubbled chins and world-weary quips, captured the soul of the American infantryman, making millions laugh, cry, and reflect from the front lines to the home front.

T

hrough Mauldin's pen, Billey embodied the unyielding spirit of the "dogface" -- the everyday soldier who endured the rain, the rations, and the relentless enemy not with glory, but with a survivor's sharp-edged humor.

Born on June 28, 1918, in Atoka County, Oklahoma, Rayson entered a world still echoing the forced relocations of the Trail of Tears. His mother, Louisa Margaret McClure Chubbee (1896–1961), carried the proud lineage of the Choctaw Nation, one of the "Five Civilized Tribes" whose lands were upended in the 1830s.

The Chubbee family, like many Choctaw, had deep roots in what became southeastern Oklahoma, a region of coal mines, cotton fields, and communities forged from adversity.

Though details of his early life remain sparse-- rural Choctaw families in the early 20th century often prioritized survival over record-keeping -- Billey grew up amid the cultural blend of tribal traditions and frontier grit. By his late teens, he had relocated to Sans Bois Township in Haskell County, a land of oak groves and winding creeks named for Oklahoma's first governor, Charles N. Haskell.

.Education set Billey apart in an era when many rural youth left school for farm work or mines. He pursued studies at the University of Oklahoma, where he delved into pictorial satire --the art of visual commentary that skewers power with a single stroke. This intellectual bent, rare for a man of his background, hinted at a mind as sharp as his bayonet.

It was this blend of scholarly depth and soldierly toughness that would later captivate a young cartoonist named Bill Mauldin.

In September 1940, as storm clouds gathered over Europe, Billey enlisted in the Oklahoma National Guard, joining Company K of the 180th Infantry Regiment in the storied 45th Infantry Division – the Thunderbirds, a unit rich with Native American recruits from tribes like the Choctaw, Kiowa, and Comanche.

The 45th, formed from Southwestern states' guardsmen, was a microcosm of America's heartland: dust-bowl farmers, oil-field roughnecks, and Indigenous warriors whose ancestors had fought in every American conflict since the Revolution.

Billey rose quickly to sergeant, his basic training prowess catching the eye of 19-year-old Private Bill Mauldin, a wiry aspiring artist from New Mexico who had joined the Arizona Guard to hone his craft.

Mauldin, who would go on to win two Pulitzer Prizes, later called Billey his "guru."

"He had lots of sides to him, this guy," Mauldin reflected. "He was my guru. He taught me about the Army and how to get along in the infantry too."

Towering and imposing -- "the biggest, meanest soldier you could imagine," as Mauldin's biographer Todd DePastino described him -- Billey was no brute. He was a voracious reader, introducing the self-taught Mauldin to masters like English satirist William Hogarth and French caricaturist Honoré Daumier.

Over barracks bull sessions and grueling drills, Billey schooled his protégé in the infantry's unspoken code: endure the officers' spit-and-polish nonsense, share the foxhole's meager comforts, and find dark humor in the chaos.

In return, Mauldin sketched Billey's hook-nosed profile and world-weary gaze, evolving it into "Willie" -- the tall, sardonic Choctaw-inspired straight man to the shorter, pug-nosed Joe's everyman woes.

These weren't sanitized comic strips for the folks back home. Debuting in the 45th Division News in 1940, Willie and Joe slouched through mud-soaked panels in Stars and Stripes, griping about cold K-rations ("Ah got a Purple Heart already – jus' gimme th' aspirin") and rear-echelon brass.

Mauldin's heavy brush strokes captured the infantryman's plight with raw authenticity, infuriating generals like George S. Patton, who once threatened to toss him in jail for "undermining discipline."

Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened, praising the cartoons as a vital morale booster. Syndicated nationwide by 1944, they reached 5 million readers, humanizing the war for a generation. Billey, ever the mentor, watched his likeness become a symbol, but as an example of every GI's quiet heroism.

War, however, demanded more than sketches. As a Type Two code talker -- part of an impromptu group using Choctaw as a natural cipher-- Billey transmitted vital messages in his native tongue during the chaos of battle.

Building on the WWI Choctaw pioneers who baffled Germans in the Meuse-Argonne, WWII's "telephone warriors" like Billey relayed coordinates and orders that enemies couldn't crack without fluency in the melodic, unscripted language.

The 45th's campaigns were unforgiving: the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, the bloody slog at Salerno, the Anzio beachhead stalemate, and the push through Cassino's rubble. Billey earned the Purple Heart for wounds sustained in these hells.

Mauldin himself was nicked by a German shell near Venafro, later joking in a strip that echoed Billey's stoicism: "Beautiful view," one officer says of the Alps, while Willie and Joe huddle in the mud below.

The war ended in May 1945, with Billey mustered out amid Europe's rubble. He returned to Keota, a tight-knit Haskell County town of 500 souls, where coal dust still hung in the air from the San Bois mines. On April 20, 1946, he married Betty Leen Francis (1925–2015), a Eufaula native whose warmth matched his quiet strength.

They built a life in Sans Bois Township, raising a family amid the rhythms of post-war Oklahoma: church suppers at the First Baptist in Keota, community barbecues, and the slow fade of the coal era as strip mining took over.

Post-war, Billey shunned the spotlight. No memoirs, no parades – just the steady work of a veteran reintegrating into civilian life. He attended the 1979 dedication of the Bill Mauldin Room at Oklahoma City's 45th Infantry Division Museum, where original cartoons line the walls like foxhole graffiti. Mauldin, by then a grizzled editorialist, reunited with his old sergeant, toasting the man who'd shaped his most famous creation.

Billey lived out his days in Keota, a pillar in a community that honored its Thunderbirds with quiet reverence. His service earned nods in Oklahoma Veterans Memorials, and Haskell County's historical markers whisper of his role in a nation that, for all its flaws, called on Native sons like him to safeguard its freedoms.

On October 24, 1989 exactly 36 years to the day before this feature's publication, Rayson Billey died at 71 in the Muskogee VA Medical Center, the same facility that had patched up countless Thunderbirds.

The Tulsa World headline captured the moment: "War hero who inspired 'Willie and Joe' dies." Mauldin, who passed in 2003, eulogized him as "a decent man, a man who killed because it was what he had to do, not because he wanted to."

Betty joined him in Keota Cemetery 26 years later, their shared headstone a simple military marker etched with Thunderbird wings.

Today, as the 45th Infantry Brigade patrols modern battlefields from the Middle East to Eastern Europe, Billey's legacy endures in more than stone. In the Bill Mauldin room, visitors trace Willie's jagged profile and see a Choctaw sergeant's face staring back, a reminder that heroes aren't born in marble halls, but in the Haskell County soil

. In an age of polished narratives, Rayson Billey teaches us: The real story of war is told not in triumphs, but in the shared aspirin and the laugh that follows the thunder.