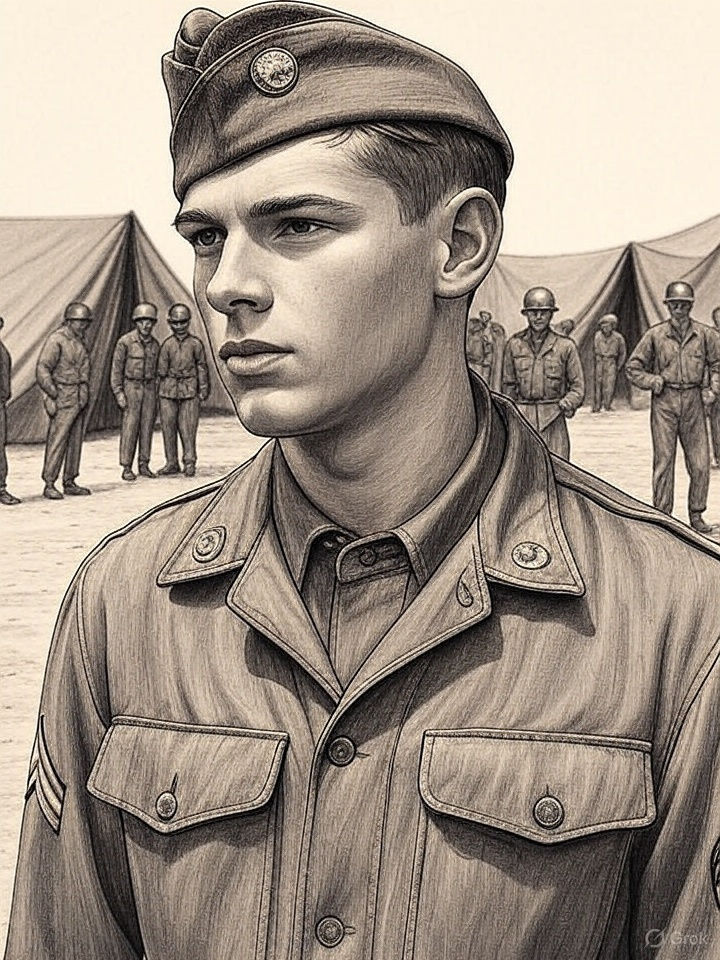

Stone Gardens: Korean War corporal from Red Oak died in Nung-dong one day after armistice agreement

- Dennis McCaslin

- Aug 31

- 4 min read

In the sweltering heat of a Korean summer, as the ink dried on a document that promised peace after three years of unimaginable carnage, Corporal Otto Vern Brown of Red Oak, Oklahoma, stepped into the misty dawn near the village of Nung-dong.

It was July 28, 1953--one day after the world believed the guns had fallen silent. But for Otto, a 23-year-old farm boy turned infantryman, the Korean War refused to end quietly.

His story, pieced together from faded enlistment papers, unit logs, and the quiet stones of a rural Oklahoma cemetery, is a poignant reminder of the "Forgotten War's" cruel coda: the armistice that saved a nation but claimed lives in its shadow.

Otto Vern Brown entered the world on January 14, 1930, in Wright City, a speck of a town in McCurtain County's piney woods, where the air smelled of sawmills and the soil clung red to boot heels.

His parents, Abel and Mary Brown, were salt-of-the-earth Oklahomans, eking out a living on modest farmland amid the echoes of the Dust Bowl. By the late 1940s, the family had moved 100 miles west to Red Oak, Latimer County--a close-knit community of 500 souls nestled in the Ouachita Mountains, where Choctaw heritage mingled with Appalachian grit.

Red Oak was no stranger to hardship; its residents had weathered the Great Depression and WWII, sending sons like Otto to distant battles.

At 18, Otto enlisted in the U.S. Army on September 2, 1948, from his Red Oak home. The world was thawing from WWII, but Cold War shadows loomed. Korea, divided at the 38th Parallel since 1945, simmered with tension between Soviet-backed North and U.S.-supported South.

Otto joined the 35th Infantry Regiment, "Cacti" for its desert roots, part of the 25th Infantry Division stationed in Hawaii and Japan. Training at places like Fort Riley, Kansas, honed him into a corporal--a squad leader ready for the rigors of infantry life.

Little did he know, his unit would soon ship out to a peninsula ablaze.

When North Korean forces stormed across the 38th Parallel on June 25, 1950, Otto's division was among the first reinforcements. The 25th arrived in July, bolstering the Pusan Perimeter--a desperate UN stand against overwhelming odds.

The 35th Infantry earned a Presidential Unit Citation there, holding the line in brutal hand-to-hand fighting. Otto, now a seasoned corporal in Company A, 1st Battalion, saw action in the see-saw battles: the Inchon landing that turned the tide, the push to the Yalu River, and the Chinese intervention that froze men in their tracks during the brutal winters of 1950-51.

By 1953, the war had devolved into a grinding stalemate. Trenches scarred the hills near the Iron Triangle, and patrols probed no-man's-land amid armistice talks at Panmunjom. The 25th Division, including Otto's regiment, rotated through sectors east of Seoul, guarding outposts against Chinese People's Volunteer Army probes.

Otto earned the Combat Infantryman Badge for frontline valor, along with the Korean Service Medal and United Nations Service Medal. His unit's tenacity--defending Seoul's approaches in May-July 1953--garnered a second Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation.

Yet, the human cost mounted: frostbite, dysentery, and the constant dread of ambush.Nung-dong, a humble village along the Han River valley southwest of Seoul, was no hotspot in 1953. But as the 25th pulled back to reserve near Camp Casey on July 8, residual dangers lingered--unexploded mines, booby traps, and the chaos of repositioning.

Otto's company conducted routine patrols, securing roads and villages in the Imjin sector.

The armistice, signed July 27 at 10:00 p.m., was meant to end it all: a DMZ drawn, prisoners exchanged, and 36,574 American lives honored.

But peace was fragile.

On July 28, Otto was near Nung-dong, perhaps on a final sweep or logistical run. Official records cite "other causes"--non-combat, but no less devastating. In the war's waning hours, such deaths were common: vehicle accidents on rutted roads, sudden illnesses in humid heat, or fatal mishaps with ordnance.

One day after the ceasefire, Otto became one of the armistice's hidden victims. His comrades in Company A mourned a quiet leader from Oklahoma, whose letters home spoke of homesickness for Red Oak's hills.

News reached Abel and Mary Brown weeks later, via telegram. Their son, who dreamed of returning to farm the family land, was gone. Otto's body was repatriated, laid to rest in Red Oak Cemetery under a simple stone etched with his rank and dates.

Otto Vern Brown's death, so close to peace, embodies the Korean War's tragedy. Over 5 million perished in the conflict--soldiers, civilians, families torn asunder. For Oklahomans, he joins 197 fallen brothers, a testament to rural America's sacrifice.

The 35th Infantry's motto, "Take Arms," echoes in his story: a corporal who served faithfully until the end.As Robert G. Ingersoll eulogized, "Cheers for the living; tears for the dead." Otto's grave in Red Oak, under Oklahoma's vast sky, weeps for the brave--one day after peace, forever honored.

In a divided Korea, his legacy reminds us: some wars end on paper, but their shadows linger.