Stone Gardens: Jack Christie-A life woven into Cherokee heritage and a traditional family legacy

- Dennis McCaslin

- 10 minutes ago

- 5 min read

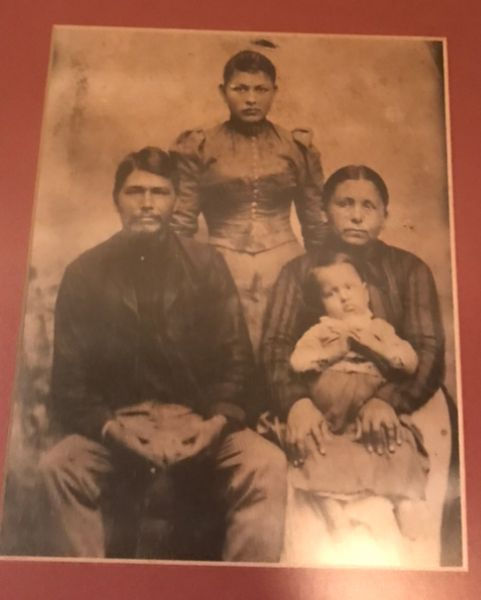

Jack Christie, born in September 1860 in what was then Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory lived a life deeply rooted in the turbulent history of the Cherokee people. As a member of a prominent traditionalist family, his story intersects with major events like the Trail of Tears aftermath, the Civil War, and the Dawes Allotment era.

Though less famous than his older brother Ned Christie, the Cherokee statesman and Keetoowah traditionalist who was branded an "outlaw" by U.S. authoritie, Jack's existence reflects the quiet endurance of Cherokee families amid forced relocation, cultural preservation, and land loss.

Jack's family lineage traces back to the heart of Cherokee Nation East, before the brutal forced removals of the 1830s. His grandfather, Lacy Christie (also known as Da-la-si-ni), was a survivor of the Trail of Tears, the infamous 1838-1839 march that displaced thousands of Cherokees westward, resulting in immense loss of life.

Lacy's wife, Quatsie "Betsy" Christie, perished en route, leaving him to raise their 13 children alone in the new Indian Territory. This tragedy was a great test of the family's spirit , as they rebuilt in the Going Snake District (near present-day Adair County.

ack's father, Wa-de Wa-ki-gu "Watt" Christie (1817-1902), embodied this spirit. Born in Cherokee Nation East, Watt was a blacksmith by trade--a vital skill in frontier communities--and a participant in the Trail of Tears as a young man. He marched westward with his first wife, Wa-da-ya (Ahnicken), and family, eventually settling in Rabbit Trap (Wauhillau), about 12 miles east of Tahlequah.

Watt's life was marked by service: He enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War at around age 41, serving as a blacksmith in Captain Budd Gritts' home guards and Company G of the 2nd Regiment of Union Volunteers, a unit composed largely of full-blood Cherokees and members of the Keetoowah Society, a traditionalist group dedicated to preserving Cherokee sovereignty and culture. Discharged in 1865 at Fort Gibson, Watt later became a political figure, elected as a Senator to the Cherokee Nation's Executive Council in 1877 and 1885.

He was known for his distrust of U.S. government encroachment and his role in protecting tribal interests

.Watt had at least 15 children across five wives, reflecting the polygamous practices sometimes seen in Cherokee families of the era. Jack's mother was Watt's third wife, Ska-ya-ht-ta "Lydia" Christie (née Thrower or Throwkiller), a Cherokee woman whose family ties deepened the clan's traditionalist leanings.

Lydia bore several of Watt's children, including Jack and his older brother Ne-de Wa-de "Ned" Christie (1852-1892), as well as siblings like Rachel, Mary, Goback, Annie, Darkey, and Jennie. The family appeared in the 1851 Drennen Roll (an early Cherokee census) in the Flint District, and by the 1890s, Watt lived in the Tahlequah District with his youngest daughter Diana, surrounded by extended kin.

This background positioned Jack within a network of Keetoowah traditionalists who resisted assimilation. The Christies were respected for their adherence to Cherokee ways, including opposition to white intruders and advocacy for tribal resources.

Watt's involvement in gold digging with his brothers in later years hints at the family's resourcefulness in a changing economy.

Born Tsa-ki-gu Wah-tie Jackson "Jack" Christie in the Tahlequah District, Jack grew up in a world of cultural upheaval alongside his brother Ned, who was eight years his senior. The post-Civil War era saw increasing U.S. pressure on Cherokee lands, culminating in the Dawes Act of 1887, which aimed to allot tribal lands to individuals and open "surplus" to white settlers.

Jack, listed as 1/2 Cherokee by blood quantum on enrollment records, was enrolled on the Dawes Roll as #29981--a process that fragmented communal lands and eroded sovereignty. He appears in multiple Enrollment Family Cards often as a parent, underscoring his role in documenting family ties for allotment purposes.

At age 45 on Card #9363, he was noted as 1/2 Cherokee, living in the Cherokee Nation.

The 1900 U.S. Census captures Jack at age 42 in Township 16N Range 24E, widowed and heading a household with four children, aided by his sister Annie Christie. This snapshot reveals a man sustaining his family through farming or traditional means in a rural, Cherokee-dominated area. His life was tied to the land around Wauhillau, a community of traditionalists where the Christies had deep roots

Jack's personal life revolved around two marriages and a prolific family, common in Cherokee households emphasizing kinship networks. His first marriage was to Jennie Tucker (born about 1856), a Cherokee woman from the Tahlequah District. They had at least 10 children, born between 1871 and 1894, many in the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory:

James Christie (November 16, 1871)

Rachel Christie (April 2, 1879)

Akie Christie (April 1881)

Katie Christie (October 1883)

Watt Christie (September 1886; another listing for September 1887 may indicate a duplicate or sibling)

Peggie Christie (1888)

Susie Christie (April 1889)

Joseph Christie (August 1891)

Thomas Christie (June 1894)

Jennie likely passed away before 1900, leaving Jack to raise the children with family support.In 1900, Jack married Nancy "Nuci Goie" Grease (or Greece, born 1863), who had been the widow of his brother Ned Christie.

This" levirate marriage"--a traditional Cherokee practice where a man married his deceased brother's widow to provide stability and support--was a profound act of family duty. Nancy had stood by Ned through his final years, and after his violent death in 1892, she brought her own children into the union. Together, Jack and Nancy had two more children:

George Christie (1901; died October 15, 1918, at age 17)

Greece Christie (1904)

This blended family lived in the Cherokee Nation, navigating the transition to Oklahoma statehood in 1907

Jack's life was indelibly marked by his brother Ned Christie, a skilled gunsmith, blacksmith, and elected Cherokee National Council member known for his fierce defense of tribal sovereignty. Falsely accused in 1887 of murdering U.S. Deputy Marshal Dan Maples (modern historians largely agree the true killer was another man, possibly influenced by alcohol and poor investigation), Ned refused surrender to what he saw as an unjust federal court in Fort Smith..

For five years, he held off repeated posses from his fortified home in Wauhillau, earning a sensationalized reputation in white newspapers as a bloodthirsty outlaw. In reality, Ned was a hero to many Cherokees for resisting encroachment.

The 1892 siege ended tragically: A large posse dynamited his home, killing Ned. His body was propped up for photographs--a degrading spectacle--and the fallout rippled through the family. Ned's young son James died under suspicious circumstances a year later, and relatives faced harassment.

By stepping in to marry Nancy and help raise the extended family, Jack quietly shouldered the burden of this trauma, ensuring continuity in a time of profound loss.

Jack lived to age 74, passing on June 4, 1935, in Oklahoma. He was buried in the family cemetery he named, Jack Christie Cemetery in Wauhillau, a site that became the final resting place for many kin, including remnants of Ned's story.

Tragically, the cemetery was bulldozed in the mid-20th century to create a pond, with most tombstones dumped into the embankment (only two recovered), symbolizing the continued erasure of Cherokee sacred spaces.

Jack Christie emerges not as a headline-grabbing figure like his brother Ned, but as the steadfast backbone of a legendary Cherokee family. He survived the fallout of Ned's stand, honored tradition by marrying his widow, and raised a large family amid the dissolution of Cherokee Nation sovereignty.

In an era of renewed interest in Native stories--through books like Devon Mihesuah's Ned Christie: The Creation of an Outlaw and Cherokee Hero or media touching on Oklahoma Indigenous history, Jack's quieter path offers a powerful counterpoint: as a man who honored kinship, and cultural continuity in the face of relentless family drama.

His descendants today carry forward this enduring legacy.