Shadows on Frog Bayou: The tragic end of George Henry and Sarah Rudy's 1870's Crawfrd County marriage

- Dennis McCaslin

- 16 minutes ago

- 6 min read

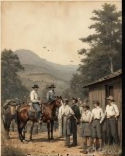

In the sweltering heat of a late summer Monday, August 20, 1877, the quiet daily motions of rural life along Frog Bayou Creek in Crawford County were shattered by a single, fateful gunshot.

Eight miles northwest of Van Buren a farmer named George Henry Rudy, a man weathered by two decades of frontier toil, turned his rifle on his wife, Sarah, ending her life in an instant of unchecked fury.

What followed was a swift unraveling of domestic tragedy into public reckoning, a case that, though brief in its legal arc, echoed the harsh realities of post-Reconstruction Arkansas: a land where family disputes simmered like the humid air, and justice was meted out with the leniency of a community reluctant to dwell on its own fractures.

Crawford County in 1877 was a patchwork of untamed wilderness and budding settlements carved from the eastern edge of the Boston Mountains in the western Arkansas Ozarks.

Formed in 1820 from the remnants of Lovely County and Cherokee lands, it had endured the scars of the Civil War with raids by Confederate guerrillas and Union forces leaving farms in ruins and families divided. By the 1870s, the county was rebounding under the shadow of Reconstruction, with Van Buren serving as a vital river port for cotton, timber, and whiskey bound for Fort Smith .

Yet, beyond the town's clapboard storefronts and steamboat docks, the countryside remained isolated, dotted with modest log cabins and cornfields clinging to creek bottoms like Frog Bayou.

George Henry Rudy (known locally as G.H. Rudy) embodied this rugged existence. Born around 1830 in Tennessee to German immigrant stock , George had migrated westward in the 1850s, drawn by cheap land grants under the federal Homestead Act.

The 1870 U.S. Census for Van Buren Township captures him at age 40, listed as a farmer with personal estate valued at a modest $300, enough for a mule, a few tools, and seed corn, but little more. Beside him sat Sarah Rudy, age 35, born in Tennessee circa 1835, her occupation simply "keeping house."

Their household brimmed with the clamor of youth: eight children, ranging from infant William (age 1) to teenager James (age 15), all born in Arkansas, a testament to the couple's determination to carve out a legacy amid the red clay soil. Sarah, whose name appears consistently as such in census rolls, though faded handwriting might render it "Saria" in hasty ledgers, was no stranger to hardship.

Like many women of her era, she managed the unseen labor of frontier domesticity: churning butter from creek-cooled milk, weaving homespun cloth from cotton bolls, and tending a kitchen garden against the threat of drought or locusts.

Marriage records from Crawford County suggest George and Sarah wed in the late 1850s, possibly in nearby Sebastian County, though exact details elude the sparse vital records of the time. Arkansas didn't mandate statewide marriage licenses until 1877, leaving much to church ledgers or county clerks' whim.

Their life on Frog Bayou, a winding tributary of the Arkansas River, was one of subsistence: corn for meal, hogs for salt pork, and the occasional barter of eggs or quilts in Van Buren.

Yet, beneath this simple lifestyl, tensions festered.

The Rudys' farm, per land patent records from the Bureau of Land Management, spanned about 80 acres, hard-won but unforgiving, prone to floods and crop failures that strained even the sturdiest marriages.

The exact spark

of that August afternoon remains lost to history, shrouded in the era's reticence about "family matters." Contemporary accounts, pieced from whispers in Van Buren taverns and the terse prose of local gazettes, pointed to a heated argument, perhaps over money. T(he Panic of 1873 had gripped the nation, driving commodity prices into the dust), child-rearing, or George's rumored dalliances with whiskey-fueled wanderlust.

Frog Bayou's isolation amplified such quarrels; neighbors were miles apart, connected only by rutted wagon trails that turned to mud in summer rains.I

.The scene was grim but uncomplicated: no signs of intruders, no robbery motive. It was, in the blunt vernacular of the time, a "husband's deed" in a spousal slaying born of passion, not premeditation. Yet, for a fleeting moment, it carried the whiff of mystery.

Rumors swirled through Van Buren: Had a lover quarreled with Sarah? Was George's confession a cover for a botched robbery? The Fort Smith New Era, the region's premier weekly (published every Thursday from its presses on Garrison Avenue), captured the shock in its August 22 edition: "

G. H. Rudy, who lived on Frog Bayou Creek, about 8 miles from Van Buren, Crawford County, killed his wife, last Monday."

The syndicated blurb, reprinted in the Jacksonport Herald on September 1, offered no salacious details--1870s journalism favored brevity over sensationalism--but it ignited gossip from Alma to Mountainburg. In a county where violent crime was more often bushwhacker ambushes than domestic implosions, the Rudy case struck a nerve, reminding settlers that the true wilderness lay not in the forests, but within the home.T

Crawford County's legal machinery, creaky as an oxcart, moved with uncharacteristic speed. George was shackled and hauled to the county jail in Van Buren, a squat stone edifice built in 1838.

Charged initially with murder under Arkansas's 1868 Penal Code (which prescribed death by hanging for premeditated killings), his fate hinged on the coroner's inquest. Held the next day by Justice of the Peace William H. Earnest, the rudimentary proceeding, witnessed by neighbors and the Rudy children, heard George's plea of accident.

Gunshot residue on his hands and the close-range wound belied any "hunting mishap," but the absence of prior threats or witnesses to malice swayed the jury toward manslaughter: an unlawful killing in the heat of sudden provocation.

By early September, the case reached the Crawford County Circuit Court, presided over by Judge J.W. Martin during the fall term. Plea bargaining, though not formalized until decades later, was the norm in rural dockets overloaded with debt claims and land disputes. George, defended by local attorney Elisha M. Harrison (a Union sympathizer known for leniency in family cases), confessed fully, sparing a full trial.

The prosecution, led by County Attorney Thomas C. Thompson, accepted voluntary manslaughter, a charge carrying 2 to 21 years under state law. On September 15, 1877, Judge Martin sentenced George to five years in the Arkansas State Penitentiary at Little Rock, a mid-range term reflecting the era's ambivalence toward "crimes of passion."

Why only five years? Context explains the mercy. Post-war Arkansas courts, burdened by Reconstruction-era backlogs, favored quick resolutions to clear dockets. Domestic violence was woefully under-prosecuted; women like Sarah were seen as chattel, their deaths a tragic footnote rather than a clarion for reform.

Similar cases abound: a 1876 Sebastian County spousal shooting drew three years, while a 1878 Franklin County axe murder got seven. George's confession and status as a "respectable" farmer and head of a large family with no prior record tilted the scales.

The children, orphaned in all but name, were parceled to kin, with the farm sold at auction to cover court costs. George served his time in the grim limestone walls of "The Rock," emerging in 1882 a broken man.

Census traces vanish after 1880 (where a "G.H. Rudy, laborer" appears transiently in Sebastian County), suggesting he drifted westward, perhaps to Texas, his legacy reduced to a probate footnote.

The Rudy case faded quickly from headlines, eclipsed by the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railway's 1878 arrival, which brought progress and more strangersto Crawford County.

No gravestone marks Sarah's resting place; likely buried unceremoniously in a family plot near Frog Bayou, her name lives only in yellowed census pages and genealogy ledgers. The children scattered: sons like James became sharecroppers, daughters wed young, perpetuating the Rudy line in diminished farms from Rudy (the town named for George's kin) to the Oklahoma border.

Yet, in the annals of Arkansas's hidden histories, Sarah's story whispers of broader truths. It underscores the invisible toll of frontier life on women, whose voices rarely pierced the patriarchal veil of 19th-century justice.

Today, Frog Bayou's banks host bass fishermen and RV parks, the cabin long rotted away.

But on quiet August evenings, when thunder rumbles over the Ozarks, locals still murmur of the "Rudy ghost", a spectral reminder that some mysteries resolve not with handcuffs, but with the slow erosion of time.