Our Arklahoma Heritage: Arkansas Titan missile silos - "Hours of boredom, moments of terror"

- Dennis McCaslin

- 8 minutes ago

- 3 min read

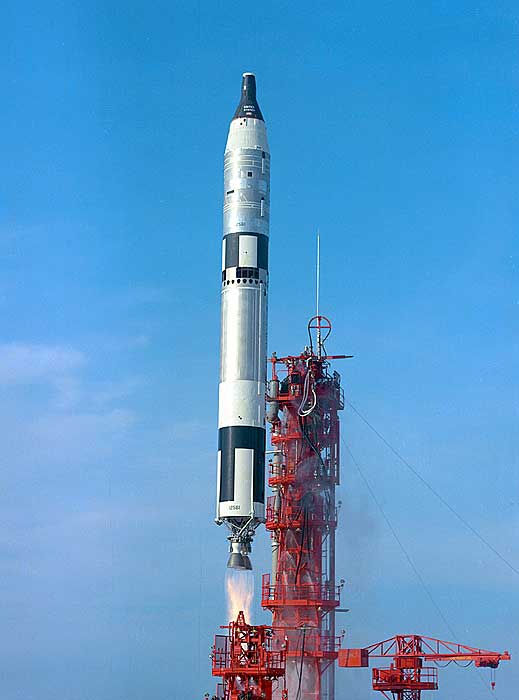

In central Arkansas, interred beneath fields of cotton and soybeans, lie the dormant relics of a Cold War arsenal. Between 1963 and 1987, this region hosted 18 subterranean silos, each housing a Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

These formidable weapons, operated by the 308th Strategic Missile Wing from Little Rock Air Force Base, were cornerstones of American nuclear deterrence, each capable of delivering a nine-megaton warhead across 9,000 miles in less than a minute.

While four of these launch complexes--373-5, 374-5, 374-7, and 373-9--have achieved designation as National Historic Places for their unique histories and preserved structures, the narratives of the remaining 14 sites, though less conspicuous, are equally integral to the state’s Cold War legacy.

The Titan II program was a direct response to the Soviet Union's successful thermonuclear test in 1953, creating an urgent demand for a missile with instantaneous launch capabilities.

Unlike its predecessors, which required time-consuming surface fueling, the Titan II was perpetually ready in its silo, armed with hypergolic propellants—a volatile combination of Aerozine 50 and nitrogen tetroxide.

The complexes, dispersed across Faulkner, Conway, White, Van Buren, Pulaski, and Cleburne counties, were feats of engineering. Each consisted of a 150-foot-deep silo connected via tunnels to a multi-level command center, where four-person crews performed 24-hour "alert" shifts, perpetually prepared for a launch order that never arrived.

The four sites listed on the National Register possess compelling histories that underscore the program's inherent dangers and historical significance.

-Launch Complex 373-5 near Center Hill (White County) is remembered for a 1968 tragedy where an airman fell to his death inside the launch duct.

-Complex 374-5 near Springhill (Faulkner County) remains sealed but is recognized for its historical integrity.

-The most infamous, Complex 374-7 near Southside (Van Buren County), was the site of a catastrophic 1980 explosion. A dropped socket punctured the missile's fuel tank, resulting in the death of Senior Airman David Livingston, injuring 21 others, and ejecting the nine-megaton warhead from the silo. The warhead's safety mechanisms prevented a nuclear detonation, but the incident accelerated the decommissioning of the Titan II program.

-In contrast, Complex 373-9 near Vilonia (Faulkner County) represents a unique form of preservation. Now known as the Titan Ranch, its renovated control center offers public tours, earning it a place on the Register in 2020 for its adaptive reuse.

The other 14 sites, while absent from the National Register, constituted the backbone of this deterrent network. Their exclusion is not a reflection of lesser importance but is typically due to post-decommissioning demolition, a lack of unique historical events, or insufficient structural integrity to meet preservation criteria.

These complexes, part of the 373rd and 374th Strategic Missile Squadrons, operated under identical high-stakes conditions. Most were deactivated between 1985 and 1987 in accordance with arms reduction treaties, their missiles removed and silos either filled or permanently sealed.

Routine operations at these sites were fraught with peril. Maintenance logs detail persistent challenges with toxic propellant leaks and electrical system failures. Minor incidents were not uncommon; for instance, a 1964 fuel leak at Complex 374-2 near Blackwell necessitated an emergency venting that narrowly averted disaster.

The psychological strain on the crews was immense, an experience one airman, quoted in David K. Stumpf’s Titan II: A History of a Cold War Missile Program, aptly described as "hours of boredom, moments of terror."

Today, the physical presence of these sites has been largely erased. Many exist on private farmland, their locations known only through historical records and GPS coordinates, with scant visible evidence beyond a concrete pad or an earthen mound. Some, like Complex 374-3 near Quitman, have been repurposed for agricultural use.

The lack of official historic status does not diminish the profound historical weight of these 14 sites. Together with the four recognized complexes, they formed an indispensable network that maintained a precarious global peace through the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

In an era of renewed global tensions, Arkansas’s Titan II sites--both listed and unlisted--serve as solemn monuments to a bygone period of geopolitical anxiety.

While the unlisted 14 may lack commemorative plaques, their subterranean remains and faded concrete pads articulate the same silent narrative: the story of a state that quietly and critically shouldered the immense burden of nuclear deterrence.