Cold Case Files: Nearly 45 years later, no one is any closer to knowing who killed 40-year-old Glenda Darlene Jones

- Dennis McCaslin

- 3 hours ago

- 4 min read

In the spring of 1980, Tahlequah was still a sleepy enclave nestled in the rolling hills of Cherokee County. With a population hovering around 10,000, it was the kind of place where neighbors knew each other's routines, and the everyday routine revolved around family farms, local schools, and the occasional community gathering.

Violence was a rarity, something read about in newspapers from bigger cities like Tulsa or Oklahoma City. But on April 9, that illusion shattered when the body of 40-year-old Glenda Darlene Nivens Jones was discovered in a well house just 300 feet from her rural home on Sleepy Hollow Road.

Strangled and left in a grotesque pose, her death ripped through the tight-knit community like a sudden storm, leaving scars that linger more than four decades later.

Glenda was born on May 25, 1939, in Texas, but she had made Oklahoma her home, building a life rooted in the soil of Cherokee County. A farm wife through and through, she managed a bustling operation alongside her husband, Frank Jones, tending to 90 head of beef cattle on their property northeast of Tahlequah.

Glenda was no stranger to hard work; she balanced the demands of ranch life with raising a family that included at least one son and three daughters. Described by those who knew her as warm and friendly, she had navigated life's complexities while maintaining a steady presence in her community.

Her brother, J.A. Nivens, lived nearby, adding to the web of familial ties that defined her world. Photos from the era show a woman with a practical demeanor, her life a tapestry of daily chores, family meals, and the quiet satisfactions of rural existence.

But what had started as a typical day ended in horror. One of Glenda's daughters made the grim discovery: her mother's nude body, stuffed head-first into the narrow pumping compartment of the well house. She had been strangled, with signs of a brutal beating evident on her body.

The scene suggested a struggle, but the remoteness of the location--tucked away on a quiet country road--meant no immediate witnesses. Cherokee County Sheriff's deputies arrived swiftly, cordoning off the farm and launching a frantic search for clues. The Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation (OSBI) was called in to assist, their agents combing the property for fingerprints, fibers, or any trace of an intruder.

Questions swirled: Had this been a random act, or something more personal? Glenda's acquaintances were interviewed, her daily routines dissected. Was it a burglary gone wrong? A crime of passion?

Evidence was scarce--no forced entry at the house, no obvious theft, just the chilling aftermath in the outbuilding.

As days turned to weeks, the investigation hit roadblocks. A suspect emerged early on, someone known in the area, but details remain murky even today. Court records and contemporary news reports indicate a trial was held, but the case crumbled under the weight of insufficient evidence. The jury couldn't connect the dots, and the charges were dismissed. Whispers in Tahlequah suggested possible motives tied to personal relationships or farm disputes, but nothing stuck.

Frank Jones, Glenda's husband, cooperated with authorities, but the family was left reeling. "It was like the ground opened up and swallowed our sense of safety," one relative later recalled in a local interview.

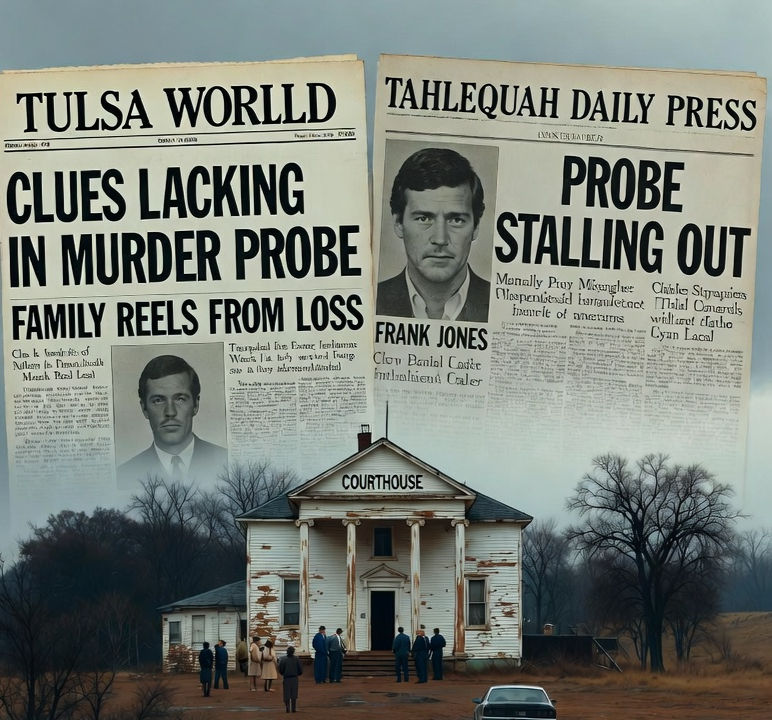

The media coverage, sparse by today's standards, painted a picture of a community in shock: headlines in the Tulsa World and Tahlequah Daily Press spoke of "clues lacking" and a probe stalling out.

For Glenda's loved ones, the pain compounded with time. Her children, still young at the time of her death, grew up under the shadow of unresolved grief. Terri Tobias, one of her daughters, has been vocal in recent years, reaching out to journalists to keep the story alive.

In 2022, she shared with the Tahlequah Daily Press: "We haven't given up hope of finding closure. It's been 42 years, but someone out there knows something."

The family pushed for answers through the 1980s and 1990s, attending hearings and pleading with investigators, but the trail went cold. Glenda was laid to rest in Tahlequah Cemetery, her gravestone a simple marker amid the Oklahoma earth she once worked.

Yet her case became an open wound, a reminder of how justice can slip away in the quiet corners of America.Decades later, advances in forensic technology have breathed new life into old files. The OSBI's Cold Case Unit, established to revisit unsolved homicides, has taken a fresh look at Glenda's murder. DNA analysis, unavailable in 1980, now offers potential breakthroughs--perhaps retesting clothing fibers or re-examining the scene with modern tools like ground-penetrating radar.

"These cases aren't forgotten," an OSBI spokesperson noted in a recent update. "A single tip could change everything."

The unit encourages anonymous submissions via email or hotline, emphasizing that even small details from the era could unlock the puzzle. Genealogical databases, which have cracked other long-dormant cases, might trace leads through familial DNA if any biological evidence from the perpetrator exists.

What haunts this story is the intimacy of the crime. The well house was mere steps from home, a place Glenda would have felt safe. Was her killer someone she knew, lurking in the familiar shadows of Sleepy Hollow Road? Or a stranger drawn by opportunity?

The lack of forced entry hints at familiarity, while the brutality suggests rage.

One persistent rumor involves acquaintances cleared early on, but without hard evidence, it remains speculation.

Jones was buried at the Tahlequah Cemetery

Today, Tahlequah has grown, its population doubling since 1980, but the memory of Glenda Jones endures as a cautionary tale. Her family continues their vigil, honoring her through quiet remembrances and public appeals.

Terri Tobias's outreach in 2022 sparked renewed local interest, prompting the Daily Press to revisit the case in a "Crime Rewind" feature. As OSBI agents apply new tools--digital reconstructions, enhanced witness interviews--the hope is that resolution will come before another generation passes.

A farm wife, a mother, a woman whose life was cut short in the prime of her years. For her loved ones, closure isn't just about justice. it's about healing.

If you have information on the murder of Glenda Darlene Nivens Jones, contact the OSBI at cold.case@osbi.ok.gov or 1-800-522-8017.

In the quiet fields of Cherokee County, a single voice could finally silence the echoes from Sleepy Hollow.